2025 Legislative Session and the State of Children’s Well-Being

May 2025

South Dakota recently wrapped up the 100th Legislative Session with 489 bills introduced.1 While only 38 days long, the Legislative Session is critical for many policies and programs that support children and families. Ultimately, we elect legislators to work on policies and draft a state budget that represents collective priorities across the state. South Dakota legislators were tasked with passing a $7.3 billion dollar budget for the next fiscal year starting this July. South Dakota’s budget is made up of:

- $2.46 billion in state funds (from sources like sales tax and one-time receipts; this projection is lower than the actual revenue from fiscal year 2024 and the projected revenue for fiscal year 2025);2

- $3.11 billion in federal funds; and

- $1.73 billion in other funds.3

With a projected decline in state revenue, legislators were faced with the difficult task of cutting the overall budget at a time when many policy bills required investment. The three departments that house the largest share of funding impacting children are the Department of Social Services, the Department of Health, and the Department of Education. Notable changes to the budget in these three departments include:

Department of Social Services (DSS):

One quarter of the state’s overall budget goes to DSS for programs like Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Child Care Assistance Program, and child protection.

Budget Brief | Approved Motion Sheets

- TANF funding from the general fund decreased by $5.3 million, shifting that money instead from TANF carryover funds which are unspent federal funds from past years. While overall funding for TANF did not decrease in the short term, a smaller state investment means lower carryover in future years and likely a decrease in funding down the road. Other states like Montana transfer some TANF money to support child care, another critical need in South Dakota.

- Medicaid (including the Children’s Health Insurance Program or CHIP) saw significant shifts in its budget, including a decrease to account for lower enrollment in Medicaid during the most recent year, a decrease in administration costs due to lower enrollment in Medicaid expansion, and a cost shift for Medicaid expansion due to federal costs covering a higher percentage of enrollees using Medicaid expansion at an Indian Health Service (IHS) facility. About a third of children in South Dakota are covered by Medicaid, down from 40 percent the year prior.4

Department of Health (DOH):

Only 2 percent of the state’s overall budget goes to the DOH, but it helps fund critical programs like home visiting (called Bright Start), WIC, and other health screening and education programs. The DOH budget changes included a minor reduction in funding for Bright Start, an increase in FTE for the newborn screening program, and, notably, a $3 million cut to the Tobacco Prevention and Reduction Trust Fund, which funds tobacco prevention efforts for all ages.

Budget Brief | Approved Motion Sheets

Department of Education (DOE):

The DOE receives the largest share of general fund spending, with nearly $800 million in state dollars supporting education across the state.

Budget Brief | Approved Motion Sheets

In addition to the budget, other policy bills impacting children and families moved through the legislative process in South Dakota, but ultimately, most of the bills we tracked failed to pass.

Missed Opportunity: Legislators Fail to Support School Meals for More Families

Unfortunately, food insecurity is a growing problem in South Dakota. The most recent data shows that 38,780 children in South Dakota, or 18 percent, are food insecure.5 About two-thirds of those experiencing food insecurity are eligible for programs like free or reduced-price meals; however, 38 percent of those children are likely ineligible for such programs.

One bill introduced this session would have taken an incremental step to help ensure families have access to affordable, healthy school meals. The House Committee on Appropriations ultimately sent this bill to the 41st legislative day.

- House Bill 1089 would have eliminated the cost of reduced-price meals for families. Families are eligible for a free meal if earning less than 130 percent of poverty (or $34,645 for a family of three) and for a reduced-price meal if earning between 130 and less than 185 percent of poverty (or less than $49,302 for a family of three). Reduced-price meals are $0.30 for breakfast and $0.40 for lunch. In the 2022-2023 school year, about 7,600 children received a reduced-price lunch each day, and about 2,700 received a reduced-price breakfast.6

House Bill 1089 was estimated to cost $616,000, a small investment to support children and families who needed it most.7 In North Dakota, families are eligible for a free school meal up to 200 percent of poverty, not only reaching more families but eliminating reduced-price costs for any eligible family.

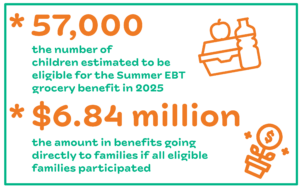

South Dakota has also continued to decline federal funding to participate in the Summer-EBT or Sun Bucks program, a grocery benefit offered during the summer for families eligible for free and reduced-price meals during the school year.8 An estimated 57,000 children in South Dakota would benefit.9 By not participating, families lose out on $6.84 million in federal funds for benefits. States must only provide the administrative cost to fund the federal program, which was estimated to be $150,000 in the summer of 2025.10 State leaders can implement this program without passing legislation. A bill was introduced and failed during the 2024 session.

Missed Opportunity: Support for South Dakota’s Child Care System Fails to Pass

Despite increased interest in supporting child care solutions across South Dakota, no bills passed to improve access and affordability of child care. Three child care bills introduced this session aimed to improve the Child Care Assistance (CCA) program, a program that helps working families pay for child care. In the most recent year, 3,067 children participated in the program in South Dakota, providing critical support to working families that need it most.11 However, many more families are eligible to receive CCA than participate, signaling additional barriers keeping families from using this program. In South Dakota, only 5 percent of eligible children participate in CCA, lower participation than all other neighboring states.12

Three proactive bills related to the Child Care Assistance program were proposed but did not pass.

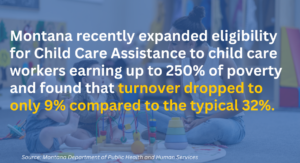

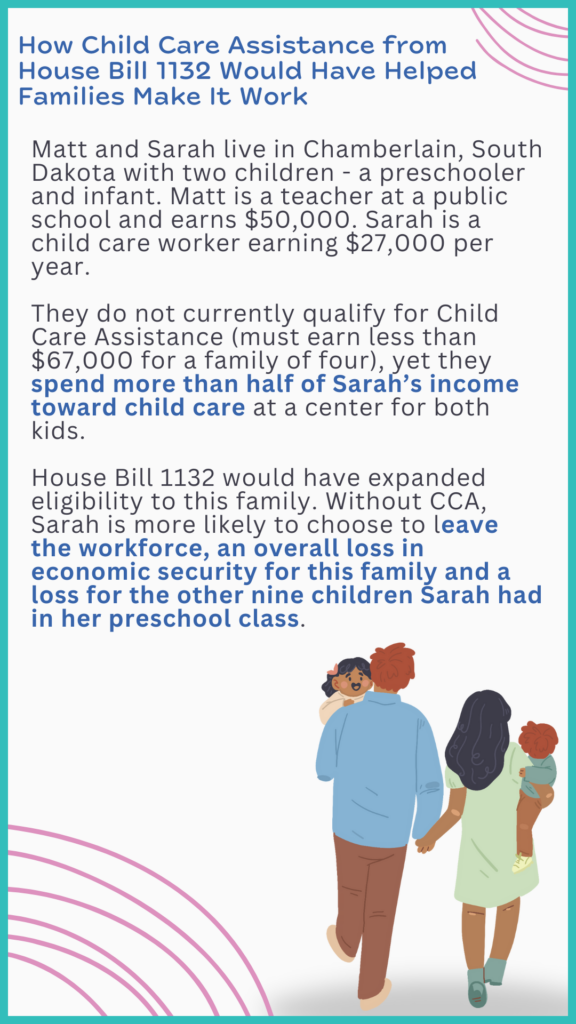

- House Bill 1132 would have expanded eligibility for the Child Care Assistance program, making child care workers eligible up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level (or around $80,000 for a family of three). While this bill passed both the House and Senate, the Governor ultimately vetoed it.

House Bill 1132 proposed a policy change that is a proven strategy in other states to improve the recruitment and retention of child care workers. In South Dakota, the median wage for child care workers is $12.92 per hour, or $26,710 on average per year.13 Given these low wages, many child care workers are already eligible for CCA. However, families where both parents work typically fall just above the eligibility guidelines but end up paying a large part of their income toward child care. When a child care worker’s own cost of care makes up most of their income, many decide to leave their role altogether. Difficulty recruiting and retaining child care workers is a key challenge for programs keeping their doors open. House Bill 1132 was a win-win solution that would have supported individual families earning low wages and all the other families that a child care worker provides care for.

- Senate Bill 126 would have raised reimbursement rates for Child Care Assistance to 90 percent of the market rate (currently at 75 percent). The current child care market is based on what parents can barely afford, not what it truly costs to provide high-quality care for children, including paying workers more than poverty-level wages. Raising reimbursement rates is an incremental strategy to match the true cost of care. For a preschool child attending a licensed program in Brookings, the rate would have gone from about $41 a day to $43 (for nine hours of care).14 Senate Bill 126 passed out of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee but was deferred to the 41st legislative day by the Senate Committee on Appropriations.

- Senate Bill 118 would have allowed graduate students to participate in Child Care Assistance, given other requirements are met. Currently, graduate students are specifically listed as ineligible. Senate Bill 118 was deferred to the 41st legislative day by the Senate Health and Human Services Committee.

Missed Opportunities: Efforts to Support Youth Mental Health Fail and Medicaid Faces Challenges

A third of South Dakota’s children are enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), helping make sure these children have access to preventive visits and other care they need while growing up.4 During the pandemic, the federal government enacted a continuous enrollment provision where Medicaid participants remained enrolled without re-determining eligibility. South Dakota began disenrolling Medicaid participants again in April 2023.15 Since then, enrollment in Medicaid has declined drastically, a trend reflected in the 2026 budget. It was well documented that many people who lost coverage during this process in South Dakota did so because of procedural reasons like outdated contact information or not understanding the process for renewal. Children were particularly vulnerable in South Dakota, where children’s enrollment in Medicaid had the largest percent change in enrollment in the country, dropping 27 percent in the first six months of this process. How Medicaid is funded, including the outreach and communication strategies used by the state, matters to ensure those who are eligible receive benefits. In the most recent data (prior to the pandemic), 11 percent of South Dakota children eligible for Medicaid are not enrolled.16

Beyond health insurance coverage, having access to the services and resources children need to grow up healthy also matters. Mental health is a growing concern for many youth; South Dakota youth report higher rates of mental health conditions compared to five years ago, with 21 percent of children and adolescents experiencing one or more mental health conditions.17

- House Bill 1077 proposed adding mental health education to the South Dakota health education standards. The current standards discuss overall health and include mental health as an education area, but mental health topics are not specifically required.18 House Bill 1077 was tabled at the sponsor's request.

- House Bill 1255 also proposed including mental health resources for students in public schools alongside age-appropriate information on consent laws. While legislators agreed that mental health education and protecting children were important, this bill was too broad and vague to accomplish that goal. The House Education Committee deferred House Bill 1255 to the 41st legislative day.

- House Joint Resolution 5001 puts an item on the 2026 general election ballot to amend the portion of the constitution that expanded Medicaid coverage to more adults, which was passed by voters in the 2022 general election. The amendment adds language that would end the Medicaid expansion program if the portion of the cost that the federal government pays drops below 90 percent. Medicaid expansion went into effect in July 2023, and about 31,000 adults are enrolled as of February 2025.19 House Joint Resolution 5001 passed both chambers and was delivered to the Secretary of State.

Mixed Bag: Legislators Defend Education Equity in Some Bills, But Fail to Make More Proactive Progress

Two bills related to education equity were introduced, supporting more inclusive environments for American Indian students. Tribal Education Departments helped lead the development of both bills, working toward an education system that reflects the values and needs of Indigenous communities.

- House Bill 1002 made a technical change to ensure that all certified educators take the existing three-credit course in South Dakota Indian studies. The current language excludes some specialists and administrators. House Bill 1002 passed both chambers and was signed by the Governor.

- Senate Bill 196 would have mandated the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings in the South Dakota education standards for both elementary and secondary students. The original bill also included language to display a poster with the Woope Sakowin, a set of values that are part of the Oceti Sakowin teachings but was amended to remove this section. Senate Bill 196 passed out of the Senate Education Committee but failed on the Senate floor with a 7-28 vote.

The Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings content standards have already been developed and were originally adopted in 2018.20 An updated version of these standards was adopted on April 14, 2025, following four public hearings, during which Tribal Chairpersons, Tribal Education Directors, educators, and families voiced strong opposition. In the final two hearings, many called for a pause in the process to allow time for Tribal consultation, as outlined in state policy. Despite this input, the board voted 5-0 to adopt the revised standards.21

Bills like House Bill 1002 and Senate Bill 196 matter because one strategy for improving academic success for American Indian students is to incorporate more culturally based education into the curriculum.22 Unfortunately, disparities continue to exist for Black, Indigenous, and children of color for education outcomes. For example, fewer than half of American Indian students graduate high school in four years compared to 84 percent overall.23 Disparities like these are a product of generations of discrimination, chronically underfunded programs promised as part of treaties between the federal government and Tribal Nations, and lack of cultural representation in public schools. A school curriculum that includes American Indian culture, heritage, and history can help Indigenous students feel a sense of belonging and improve their academic success.24 Additionally, ensuring public schools and educators have the training and resources to fully implement curriculum like the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings is one way to foster a more culturally relevant education for the 13,500 Indigenous students attending public schools in South Dakota.25

Numerous other bills were introduced that threatened education equity in South Dakota. While these bills ultimately did not pass, they reflect a growing trend toward policies that create exclusionary conditions for Indigenous and LGBTQ+ students.

- Senate Bill 51 would have required school districts to display the Ten Commandments alongside additional background on the Ten Commandments. This bill also requires the history and civics curriculum to include the Ten Commandments, the state and U.S. Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and other documents determined by the South Dakota Board of Education Standards. Senate Bill 51 narrowly passed the Senate but ultimately failed in the House.

- House Bill 1201 and House Bill 1177 both would have created a less inclusive environment for all students. House Bill 1201 would have required school counselors to obtain parental consent prior to working with a student and enacted new requirements for notifying parents about certain content discussed during counseling sessions, including conversations related to gender identity.

House Bill 1177 made it so teachers or students would not receive any disciplinary actions if they did not use another person’s preferred name and pronouns. Both House Bill 1201 and House Bill 1177 failed to pass out of the House, important victories to ensure students of all gender identities are welcome in South Dakota schools.

While the 2025 session has wrapped up, the work to advocate for stronger policies for children continues. State agencies administering programs have a wide range of authority to make rules at the state level that would better support families. South Dakota’s 101st Legislative session will begin at the beginning of 2026.

Footnotes

- South Dakota Legislative Research Council, “2025 Bills.” There were 269 House Bills and 220 Senate Bills introduced and a handful of other commemoration or joint resolutions as well.

- South Dakota Legislative Research Council, “Subcommittee on Revenue Projections,” Feb. 13, 2025. The $2.46 billion state revenue projected for fiscal year 2026 is a decrease compared to the actual revenue from fiscal year 2024 ($2.54 billion) and the projected revenue for fiscal year 2025 ($2.65 billion).

- South Dakota 100th Legislature, “An Act to appropriate money for the ordinary expenses of the legislative, judicial, and executive departments of the state, the current expenses of state institutions, interest on the public debt, and common schools,” SB 220, enacted on Mar. 28, 2025.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Participants by Age Group in South Dakota,” 2024.

- Feeding America, Map the Meal Gap, “Food Insecurity among the Child Population in South Dakota,” 2022.

- FitzSimons, C., Hayes, C., “The Reach of School Breakfast and Lunch During the 2022-2023 School Year,” Food Research & Action Center, Mar. 2024.

- Grant Judsen, Bureau of Finance and Management, testimony on House Bill 1089, House Education Committee, Feb. 3, 2025. (1:46 of recording).

- United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, “SUN Bucks (Summer EBT),” accessed on Apr. 3, 2025.

- Food Research & Action Center, “The Summer EBT Program Would Reduce Summer Hunger in South Dakota,” Dec. 2024.

- Rep. Duba, L., “Require the Department of Social Services and the Department of Education to apply for and administer the summer electronic benefit transfer for children program and to make an appropriation therefore,” HB 1184, South Dakota 99th Legislature, as passed by the Joint Committee on Appropriations (Amendment 1184B) on Feb. 23, 2024.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Child Care Assistance Recipients in South Dakota,” 2024.

- South Dakota KIDS COUNT, “Child Care Assistance: An Updated Look at the Data,” Jan. 2025.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics,” May 2024.

- Department of Social Services, Division of Economic Assistance, Child Care Services, “South Dakota Child Care Market Rate Report,” 2024.

- South Dakota KIDS COUNT, “Medicaid Expansion: Opportunities to Improve Enrollment,” Mar. 2024.

- KFF, “State Health Facts, Medicaid/CHIP Child Participation Rates,” accessed on Apr. 3, 2025.

- Population Reference Bureau analysis of National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016, 2017, 2021, 2022 enhanced files, on file with author.

- Department of Education, “South Dakota Health Education Standards.”

- Department of Social Services, “DSS Statistical Information.”

- Department of Education, “South Dakota Content Standards,” accessed on Apr. 3, 2025.

- South Dakota Board of Education Standards, “Meeting Minutes, April 14, 2025.”

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding shortfall for Native Americans,” Dec. 2018.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Four-year High School Cohort Graduation Rate By Race/Ethnicity in South Dakota,” 2023/24.

- EdNote, “The Importance of Providing Native American Education for All Students,” Dec. 16, 2019.

- South Dakota Department of Education, “Enrollment for Public Schools,” 2024/25.