Medicaid Expansion: Opportunities to Improve Enrollment

March 2024

South Dakotans voted in 2022 to expand Medicaid, making 51,000 adults newly eligible for affordable and comprehensive health insurance. Having health insurance improves financial security, protecting people from high medical costs and any resulting medical debt when they receive care, but it does more than save people money.1 People with health insurance are more likely to receive preventative services and have better health outcomes than their uninsured peers.2 Expanding access to Medicaid is a first step to ensure more adults have affordable health care. With only 39 percent of eligible people currently enrolled in Medicaid expansion, effective outreach and enrollment strategies are necessary to maximize the benefits for South Dakotans.

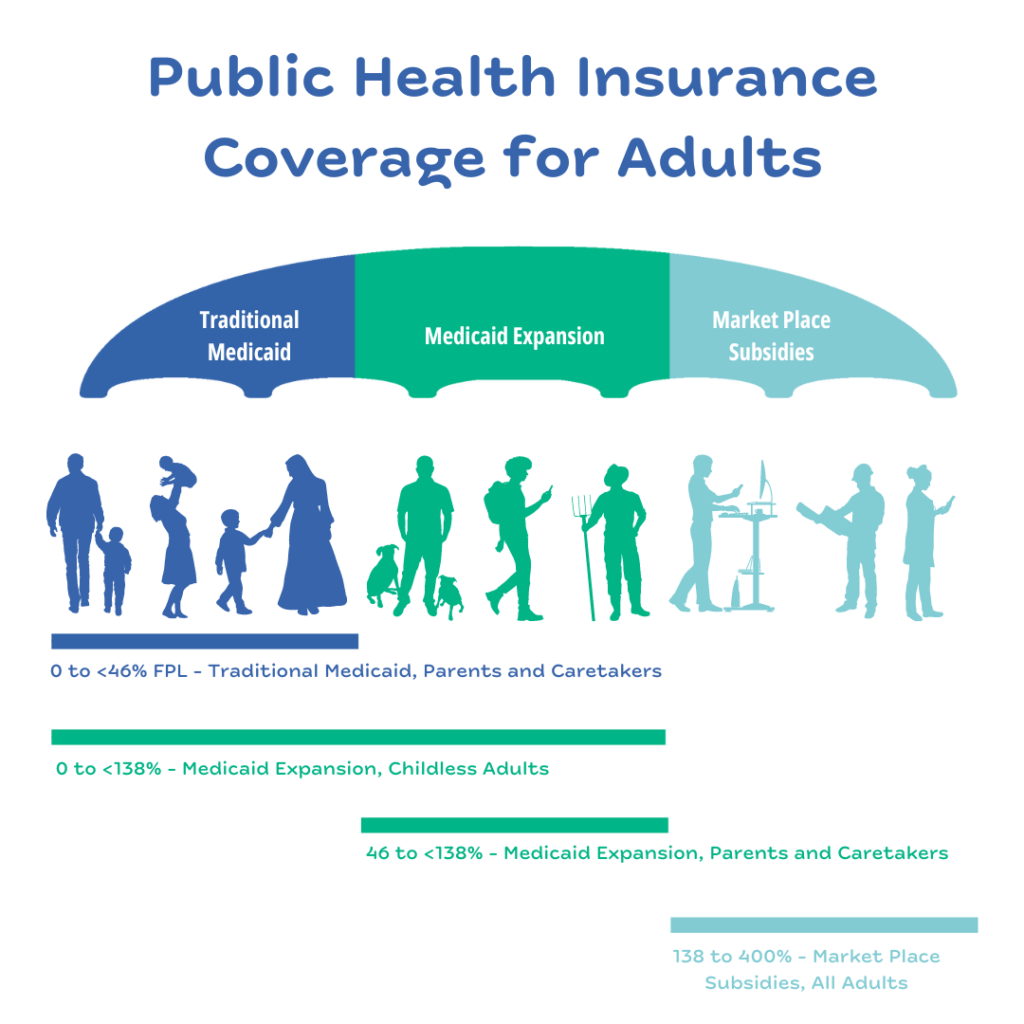

South Dakotans Have More Options for Affordable Health Insurance

Individuals in South Dakota have more options than ever for affordable health insurance after voters passed Medicaid expansion. As of July 1, 2023, South Dakota adults are eligible for Medicaid if they make less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or up to $43,056 for a family of four.3, 4 Before Medicaid expansion, adults without children were not eligible for Medicaid at any income level, and parents were only eligible at less than 46 percent of the federal poverty level, or $14,352 for a family of four.

People earning 138 percent of the federal poverty level or more in South Dakota are eligible for federal Health Insurance Marketplace coverage. While some adults may receive health coverage through their employers, workers in low-paying fields or who work part-time are less likely to receive employer-sponsored insurance.5

During the pandemic, the federal government enacted a continuous enrollment provision where Medicaid participants continued to remain enrolled without re-determining eligibility. South Dakota began disenrolling Medicaid participants again on April 1, 2023, a process also called unwinding of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision.6 As South Dakota begins re-determining eligibility for Medicaid, some participants are getting lost in the process. As of November 2023, more than half (51 percent) of the 54,500 participants who lost coverage did so because of procedural reasons, like outdated contact information, not understanding the process for renewal, or not completing the renewal in the allotted timeframe.7 Children have been particularly vulnerable during this process in South Dakota, where children’s enrollment in Medicaid had the largest percent change in enrollment in the country, dropping 27 percent in the first six months of the unwinding (27,572 fewer children were enrolled in September 2023 compared to March 2023).8 Because of Medicaid unwinding, fewer people were enrolled in Medicaid at the end of 2023 than at the start of the year, even with the added enrollment from Medicaid expansion.9

Medicaid unwinding is another layer of the health insurance story in South Dakota as people may lose coverage during this process who are still eligible for Medicaid or newly eligible through Medicaid expansion. The drastic drop in enrollment because of Medicaid unwinding underscores the importance of outreach and communication strategies for people accessing Medicaid. Young adults could be particularly vulnerable during Medicaid unwinding as teenagers enrolled in Medicaid in 2020 have now transitioned into adulthood, with new or changing contact information or responsibility for obtaining their own health insurance for the first time.

Young Adults Are the Most Likely Age Group to Be Uninsured

Expanded eligibility for Medicaid in South Dakota has the potential to impact coverage rates for young adults (those age 19 to 25). Young adults have the highest rate of uninsurance compared to all other age groups, and the rate more than doubles compared to children age 6 to 18 (18 percent for young adults compared to 7 percent for school-age children).10 Health insurance coverage for young adults has increased in the last decade, an improvement largely credited to the Affordable Care Act’s provision for young people to stay on their parent’s health insurance until age 26.11 However, staying on a parent’s insurance is not an option for every young adult, with higher-income families more able to utilize this option than lower-income families.

Young adults are in a time of transition - some have full-time employment with access to health insurance through their employer. Others attend postsecondary education and may have access to a student insurance program through their school. However, many other young adults lack access to employer or school-based health insurance options. In South Dakota, 14 percent of adults age 20 to 24 are not connected to school or employment.12 During this time of transition, young adults set a foundation for their future health and economic success. South Dakota can ensure eligible young adults know about and are enrolled in Medicaid to support them during this transition.

Medicaid Expansion Provides Key Access to Health Services in Indian Country

Everyone should be able to live a healthy life, but ongoing discriminatory government policies continue to impact the health and well-being of American Indian people today. Indigenous South Dakotans have a median age of death that is 22 years shorter than their white peers.13 American Indian or Alaska Native young adults are uninsured at a rate more than three times higher than all young adults, with more than half (55 percent) lacking comprehensive health insurance.14

The federal government is obligated to provide health care to American Indians as part of trust responsibilities originally established through treaties with tribal nations. Through these treaties, tribal nations ceded control of millions of acres of their homelands to the United States in exchange for compensation and services, including medical services. The federal government has failed to fully meet its legal obligation to provide comprehensive health care services to citizens of tribal nations.

Tribal health providers include the Indian Health Service (IHS), Tribally-run health facilities, and clinics run by Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs). These three components are collectively referred to as “I/T/U.” The federal government has chronically underfunded the IHS, Tribal health facilities, and UIOs. IHS receives only 57 percent of the per-person funding as Medicaid (per-person expenditures are $4,078 for IHS and $7,106 for Medicaid), and UIOs only receive 1 percent of the IHS budget.15, 16, 17 Underfunding of these I/T/U health services means comprehensive care is not consistently available for American Indians when they need it. Since the IHS is not an insurance program and because limited funding means comprehensive health services are not universally available, those who rely on IHS alone are not considered to have health insurance in the available data.

IHS, Tribal health, and UIO clinics are a critical part of health care in Indian Country. There are more than 20 IHS or tribal facilities located within South Dakota and two UIO clinics located in Pierre and Sioux Falls.18 Expanded eligibility for Medicaid means more federal dollars are available to support tribal facilities in South Dakota. For example, when a Medicaid enrollee receives services from an IHS facility, Medicaid reimburses that expense rather than it coming out of the IHS budget. Even more, the federal government covers 100 percent of the Medicaid reimbursement for care provided to American Indians at an IHS facility, where typically the state must also cover a portion of the cost. This cost shift is significant for access to health care in Indian Country. After Montana expanded Medicaid, additional funding for IHS facilities translated to offering more services like preventative screenings, mental health treatment, and substance use disorder treatment.19 In the six years since Medicaid expansion in Montana, preventative services for American Indian enrollees doubled while mental health and substance use disorder treatments nearly tripled.

Medicaid expansion has the potential to shift access to health care coverage significantly and expand health services in Indian Country. Outreach to eligible participants who are American Indian is a critical step to begin undoing the harm done over generations of systemic discrimination for Indigenous people and begin supporting access to comprehensive health services in Indian Country.

Thousands of People Are Eligible but Not Enrolled in Medicaid Expansion

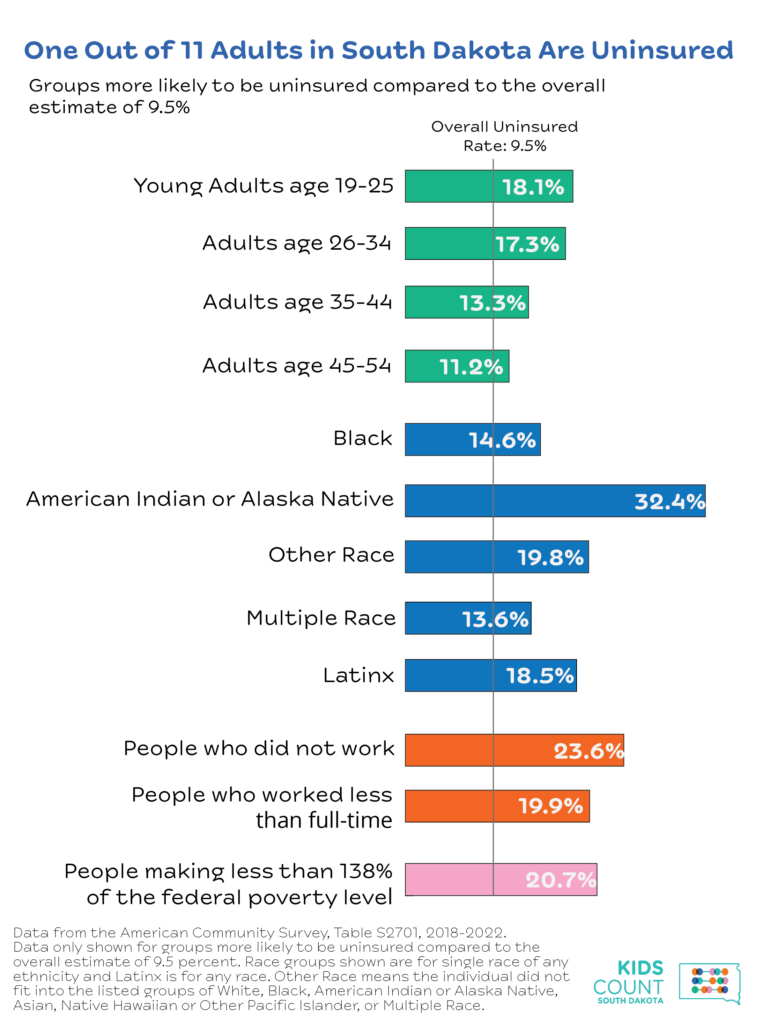

Before Medicaid expansion, one out of 11 people (9.5 percent) in South Dakota lacked health insurance.20 Certain groups are more likely to be uninsured including working-age adults, people who did not work or who work less than full-time, and those making less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Black, Indigenous, Latinx and those identifying as other or multiple races also have higher uninsured rates.

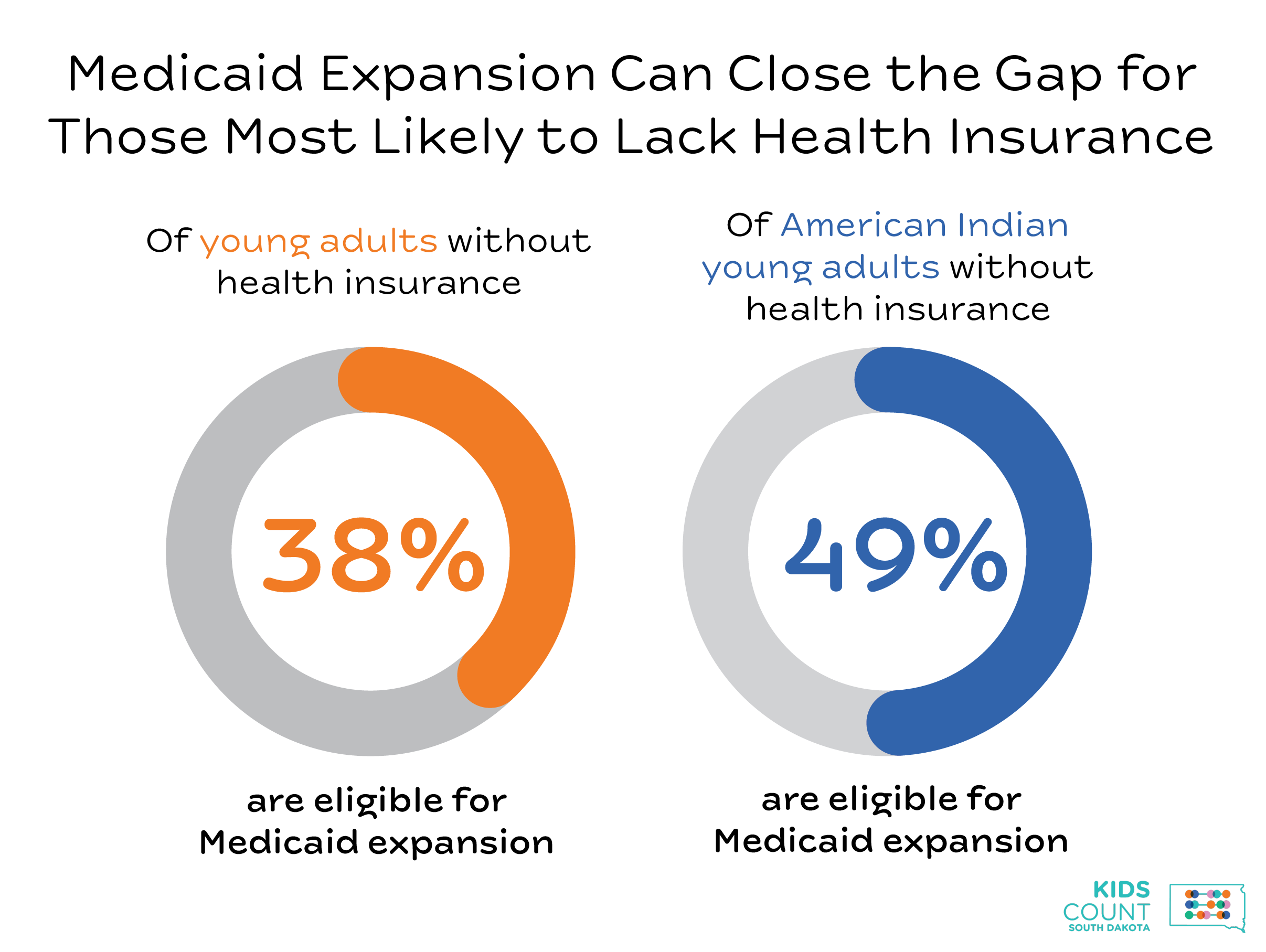

While the uninsured rate in South Dakota has improved in the last decade, gaps in coverage exist across different groups and geographies in the state. Medicaid expansion coverage can help close the gap for those most likely to lack health insurance. For example, of the young adults without health insurance in South Dakota, 38 percent are eligible for Medicaid expansion.21 Nearly half (49 percent) of uninsured American Indian young adults are eligible for Medicaid expansion.22

Effective outreach and enrollment are key to reaching uninsured individuals eligible for Medicaid. In the first seven months of expanded Medicaid enrollment, 19,811 individuals enrolled in Medicaid expansion coverage.23 This represents 39 percent of those estimated eligible (51,000) overall.24 As a comparison, when Montana expanded Medicaid eligibility in 2016, 62 percent of those who were anticipated eligible were enrolled in the first seven months.25

Those identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native have the highest enrollment compared to the eligible population, with 80 percent currently enrolled.26, 27 This trend for American Indian people is significant, given the opportunity Medicaid expansion has to impact health care in Indian Country. Overall, young adults do not fare as well, where only one out of five young adults eligible for Medicaid expansion is currently enrolled.28, 29 Enrollment compared to the eligible population varies widely across the state, ranging from enrolling only 14 percent of those eligible in Brookings county up to 82 percent in Buffalo county.30, 31 No county has enrolled all of the eligible population, indicating a need for continued outreach across the entire state, but more focused outreach may be needed in certain areas.

More Automatic Enrollment Systems and Outreach Strategies Are Needed to Improve Enrollment for Young Adults

The benefits of Medicaid expansion to individuals and the state rely largely on enrolling those who are eligible. State leaders should consider first how to build more automatic processes into their systems that identify and enroll eligible participants. Second, the state can work alongside community organizations to conduct outreach to eligible populations that may be missed through more automatic enrollment.

South Dakota should consider ways to streamline enrollment in Medicaid expansion wherever information about eligible participants already exists. For example, parents applying for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) for their kids could also be automatically assessed for Medicaid eligibility. Individuals receiving unemployment insurance benefits could also be automatically assessed for Medicaid eligibility. Other programs like SNAP or WIC provide opportunities for the state to consider where there is overlap in eligibility for Medicaid. Information across programs often exists in different agencies and data systems, but collaborating across agencies and working to share data is a proven strategy used in other states to boost enrollment.

More immediately, states can commit resources and work alongside community organizations to reach eligible but unenrolled populations across the state. Considering the high uninsured rate of young adults, specific outreach strategies are needed to reach a younger audience.

For communication about eligibility or benefits, using texting or email instead of mailing information is one way to reach more young people. Broader campaigns should consider using social media platforms that more young people are on, including Instagram and Tik Tok. Outreach events at places like universities, tribal colleges, or community colleges are a good place to start, but not every young adult is connected to higher education. Working with child care and elementary schools can help reach young parents with information about eligibility. Young people often work in service industry jobs that may not offer employer-sponsored health benefits, so working with local businesses or Chambers of Commerce to share information could reach more working young adults. Through all these strategies, focusing messaging on what matters most to young adults including the affordability of Medicaid and relevant services like mental health treatment, birth control, or emergency services. Last, who knows young adults best? Young adults. Working with young adults in outreach and messaging efforts can be a key strategy to improving health care coverage for this age group.32

The State Should Act Now to Improve Outreach and Enrollment

Access to health insurance builds a stable foundation for people and improves their economic security and health. With expanded eligibility for Medicaid, accessing health insurance is within reach for more South Dakotans than ever before. Strategies to improve outreach and enrollment help support a healthy workforce and healthy families. State policymakers should consider the following recommendations to enroll more individuals eligible for Medicaid expansion:

- Implement outreach campaigns designed to reach populations with less access to health insurance including young adults, part-time or low-wage workers, and Black, Indigenous, and other people of color;

- Identify ways to streamline eligibility and outreach. For example, identifying individuals most likely eligible for Medicaid expansion such as those claiming uninsurance benefits, parents applying for Medicaid or CHIP for their children, or those participating in SNAP, WIC, or free and reduced-price lunch; and

- Partner with local communities to increase outreach capacity where there is low enrollment compared to the eligible population.

Footnotes

- Lukens, G., “Montana’s Fiscal Gains From Medicaid Expansion Are a Model for Wyoming,”Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Sep. 15, 2022.

- American Hospital Association, “The Importance of Health Coverage,” Oct. 2019.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2024,” accessed on Feb. 14, 2024.

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “Medicaid Expansion Eligibility.”

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Health Insurance Coverage Status and Type by Work Experience, 2022, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table C27012.”

- KFF, “10 Things to Know About the Unwinding of the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision,” June 9, 2023.

- KFF, “Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker,” accessed on Feb. 14, 2024.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “New State by State Analysis on Impact of CMS Strategies for States to Protect Children and Youth Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment,” Dec. 18, 2023.

- Department of Social Services, “DSS Statistical Information,” accessed on Mar 11, 2024.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Selected Characteristics of Health Insurance Coverage, 2018-2022, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S2701.”

- Gangopadhyaya, A., Johnston, E., “Expanding Medicaid in Additional States Could Improve Insurance Coverage and Access to Care Among Young Adults in Low-Income Households,” Urban Institute, Feb. 22, 2021.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Youth Not Attending School and Not Working by Age Group in South Dakota,” 2022.

- South Dakota Department of Health, “American Indian Health Data Book,” Jan. 2024.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, Vintage 2022. Of the 7,715 American Indian or Alaska Native young adults, 4,260, or 55 percent, lack health coverage. Race is defined as American Indian or Alaska Native alone across both ethnicities.

- Indian Health Service, “IHS Profile,” accessed on Feb. 14, 2024.

- KFF, “Medicaid Spending Per Full-Benefit Enrollee,” 2019.

- Indian Health Service, “Fiscal Year 2024 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees,” Mar. 10, 2023.

- Indian Health Service, “Indian Health Service Health Care Facilities,” accessed on Feb. 14, 2024. Great Plains Tribal Leaders Health Board, “Great Plains Area Health Care Sites.”

- Montana Healthcare Foundation, “Medicaid in Montana, How Medicaid Impacts Montana’s State Budget, Economy, and Health, “ 2023.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Selected Characteristics of Health Insurance Coverage, 2018-2022, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S2701.”

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, Vintage 2022. Of the 13,533 young adults without health insurance, 5,097 fall between 0 and 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, Vintage 2022. Of the 4,260 American Indian young adults without health insurance, 2,103 fall between 0 and 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “DSS Statistical Information,” accessed on Feb. 21, 2024.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, Vintage 2022. An estimated 31,707 individuals age 19 to 64, without children or a disability who fall between 0 and 138 percent of the federal poverty level. An additional 19,547 individuals age 19 to 64 without a disability but with children who fall between 47 to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. In total, 51,254 individuals are estimated to be eligible for Medicaid expansion coverage.

- Poulette, J., Legislative Fiscal Division, “RE: monthly enrollment in MedEx,“ email to Heather O’Loughlin, MBPC, Oct. 26, 2023, on file with author.

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “DSS Statistical Information,” accessed on Feb. 21, 2024.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, Vintage 2022. An estimated 3,756 American Indian individuals age 19 to 64, without children or a disability who fall between 0 and 138 percent of the federal poverty level. An additional 5,333 American Indian individuals age 19 to 64 without a disability but with children who fall between 47 to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. In total, 9,089 American Indian individuals are estimated to be eligible for Medicaid expansion coverage.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample, Vintage 2022. An estimated 14,648 young adults age 19 to 25, without children or a disability who fall between 0 and 138 percent of the federal poverty level. An additional 3,952 young adults age 19 to 25 without a disability but with children who fall between 47 to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. In total, 18,600 young adults are estimated to be eligible for Medicaid expansion coverage.

- Lippert, J., “RE: Informal Request for Information PUBRECREQ0001530,” South Dakota Department of Social Services, Feb. 7, 2024. Data was provided to the author for the number of Medicaid expansion enrollees age 19 through 25 as of January 2024.

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “DSS Statistical Information,” accessed on Feb. 21, 2024.

- Estimates for the population eligible for Medicaid expansion by county is calculated as: 51,254 * percent of people age 18 to 64 living below 150 percent of the federal poverty level. U.S. Census Bureau, “Age by Ratio of Income to Poverty Level in the Past 12 Months, 2018-2022, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B17024.”

- Schultz, M., Conversation on best practices for working with youth, “Kids Count/YI Connect,” Oct. 31, 2023.