Child Care Assistance Program: An Opportunity for South Dakota to Improve the Child Care System

January 2024

Children make up nearly a quarter of South Dakota’s population.1 Many of these children live in families that need or want some form of child care to pursue work, training, or education opportunities. In 2022, three out of four young children in South Dakota lived in families where all available parents worked.2 However, finding and affording childc care is challenging across the state. Families are left to sift through a patchwork of regulated and unregulated care, waitlists, and ultimately pay high costs when they do find care.

These challenges are not unique to South Dakota. Families across the country grapple with finding and affording child care. Additional federal funding available during the pandemic provided needed support to child care programs, but much of that funding has been spent. Other states are stepping up to make investments to continue supporting the child care industry. South Dakota can do the same and recognize child care as an essential support for children, families, and businesses.

Child care in South Dakota is a patchwork of regulated and unregulated care.

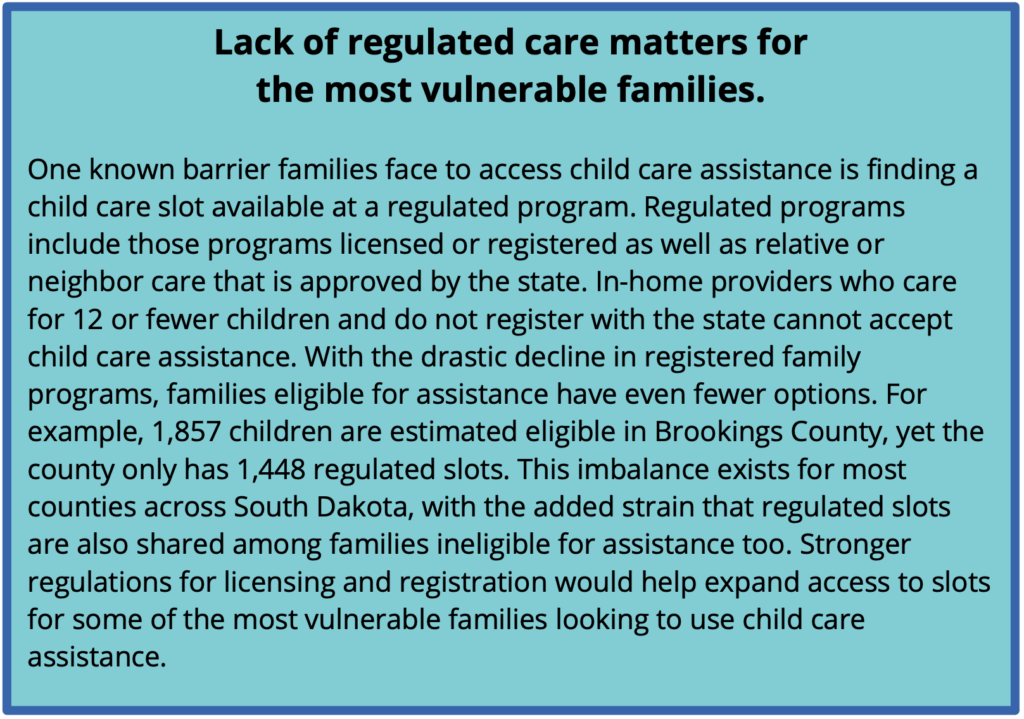

The Department of Social Services in South Dakota regulates child care programs including licensed school-age programs, licensed center or family-based programs with 13 or more children, and a voluntary registration for family-based programs with fewer than 13 children.3 Unregulated care exists in South Dakota, but a lack of data on these programs makes it difficult to understand where and how many unregulated programs provide care.

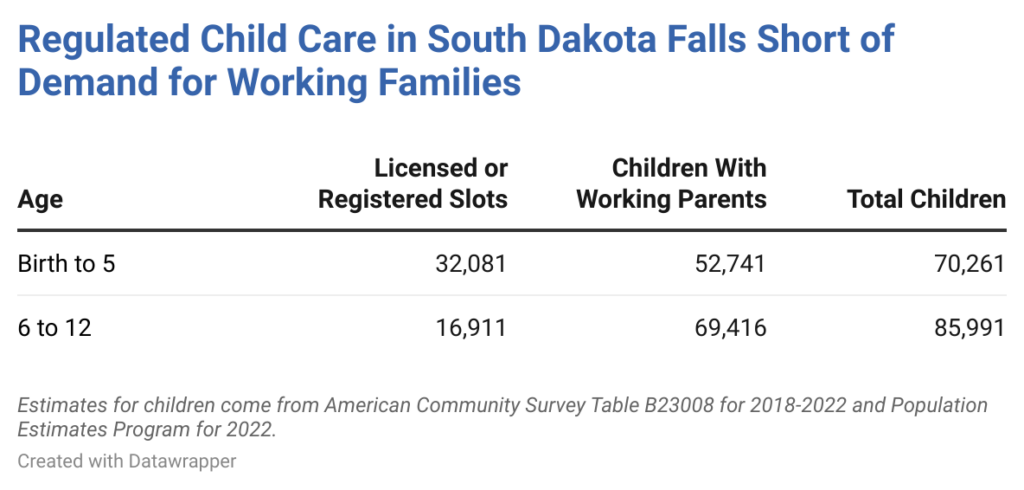

In 2023, 780 programs were licensed or registered with the state providing slots for 16,911 school-age children and 32,081 slots at a family or center-based program.4 Family homes that voluntarily register with the state have declined in the last decade, with only half the number of registered programs in 2023 (368 registered programs) compared to 2013 (749 registered programs). Since program registration is voluntary, it is impossible to know whether this decline is due to fewer family-based programs with less than 13 children existing, or if fewer programs are choosing to register.

Access to child care programs varies across the state. Five counties have no regulated child care programs at all.4,5 How the supply of child care meets the current demand across the remaining counties is hard to assess in South Dakota without more comprehensive data on unregulated care. A survey in Brookings from 2020 found that 36 percent of families used unregistered family child care, and 12 percent used a family or friend, leaving about half of the child care slots not captured in the statewide data.6 After adding in the additional, unaccounted-for slots, the child care supply in Brookings likely met closer to 90 percent of the demand for working families.7 Despite meeting an estimated 90 percent of demand, families in Brookings reported a disconnect between their current child care arrangement and preferred arrangement. The most commonly reported type of child care was an unregistered family home, yet only 3 percent said this was their preferred arrangement. While Brookings falls just short of the estimated child care demand, a more important question may be whether the current supply of child care reflects families’ needs and preferences.

Child care makes up a big expense for families in South Dakota.

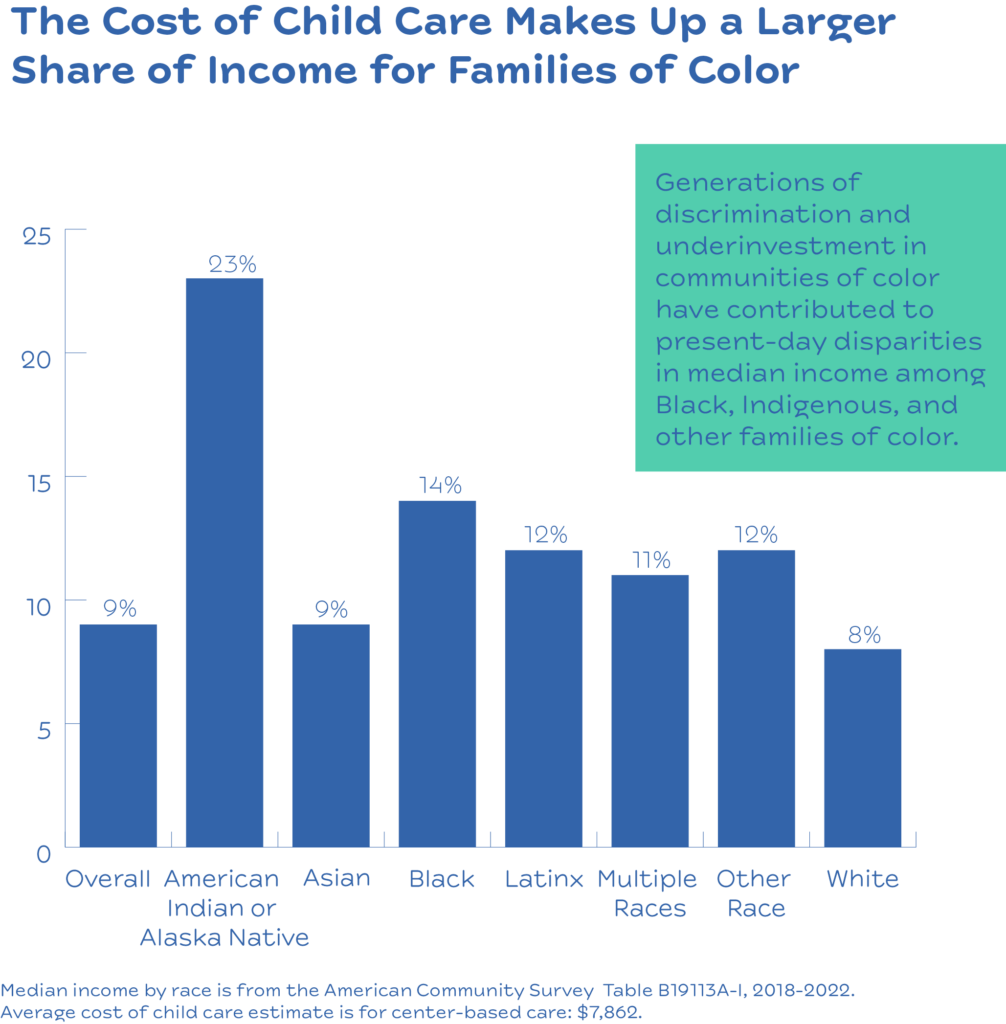

For families that do find child care, the cost is often out of reach. The cost for full-time child care varies based on age, the type of facility, and geographic location within South Dakota. Parents pay, on average, $7,862 per year for center-based care and $5,824 per year for family-based child care.8 However, local rate surveys show that costs are significantly higher in Sioux Falls, where parents pay $7,785 on average per year for an in-home program and $12,400 on average per year for a center-based program.9

Access to affordable child care is a racial and economic justice issue. For many families, child care is an essential tool needed to pursue education, training, or work opportunities. Over many decades, Black, Indigenous, and other families of color have been denied opportunities to pursue education or other economic opportunities, resulting in present-day disparities in median income. As a result, child care is disproportionately more unaffordable for families of color. The average cost estimate for center-based care ($7,862) makes up 9 percent of a typical family’s income.10 The cost of child care for Black, Indigenous, and other families of color makes up a larger share of their income, putting child care further out of reach for these families. When child care is less accessible for families of color, it perpetuates the cycle of having limited opportunities to work or continue their education.

While child care makes up a big expense for families, child care workers make low wages despite the value of their essential work. The reality of today’s child care profession has been shaped by decades of policies and public perception that devalued the role of caring for young children. For example, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 excluded domestic, agricultural, and service occupations.11 This exclusion marks one policy decision that undervalued caregiving work, and was particularly harmful for Black, Indigenous, and other women of color who had been forced into domestic and caregiving work throughout history. There are centuries of other examples of policies that set the precedent for undervaluing caregiving as a skilled and essential role. This legacy of policies shapes the present-day reality of an underpaid and undervalued child care workforce.

Child care programs are left to figure out how to balance the true cost of providing high-quality care with what parents can afford. This often means providers struggle to offer competitive pay and benefits to their staff. In 2022, the median wage for a child care worker in South Dakota was $11.97 per hour, the second lowest median wage for any occupation.12 This translates to $24,900 per year if working full-time, hovering at the poverty level for a family of three.13 While wages for child care workers in South Dakota have increased in the last three years, these increases have merely kept up with increased costs due to inflation. The median wage from 2020 ($10.39) adjusted for inflation to May 2022 is $11.84, meaning current wage levels of $11.97 have increased by only $0.13 factoring in inflation.14,15 Low wages for child care workers leads to staffing instability, making it challenging for child care businesses to retain workers and remain open. More than half of licensed programs reported a lower enrollment than desired in 2022 with the primary reason being a lack of staff.16

Improving the Child Care Assistance Program supports families and providers.

The Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) is one opportunity to improve South Dakota’s child care system. The CCAP is primarily funded through a federal block grant, with most funds distributed as subsidies to help families with low incomes pay for child care. The same block grant also supports child care regulation and promotes program quality. Child care assistance looks different across states with a lot of flexibility given to state policymakers to set eligibility requirements, copayment amounts, and other participation details.

In South Dakota, a family is eligible for the CCAP if they:17

- Earn less than 209 percent of the federal poverty level, or less than about $52,000 per year for a family of three;

- Work at least 80 hours per month or attend an education or training program; and

- Have a child, age 12 or younger, or an older child with special needs.

Children in foster care are also eligible for the CCAP without a family meeting the income or work criteria. A child eligible for the CCAP must attend a regulated child care program, and the provider receives a reimbursement from the state for the care provided. Some families pay a small copay, which costs no more than 1 percent of the family income. For example, a family of three with an income at the highest eligibility level pays a $40 monthly copay.18

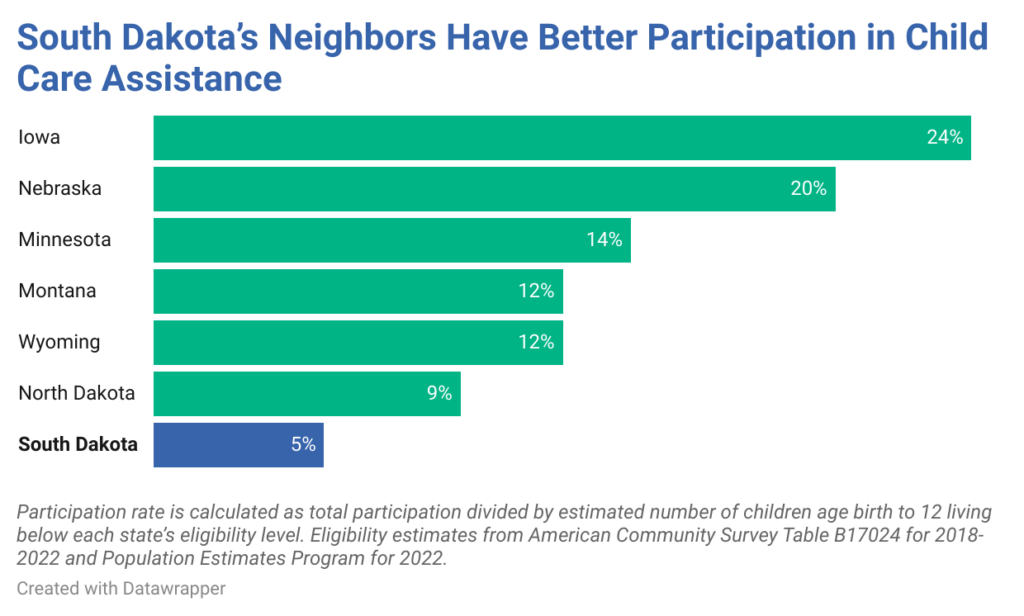

In state fiscal year 2023, 2,941 children participated in the CCAP in South Dakota.19 Fewer children participate in the CCAP than a decade ago, with participation down by 40 percent. Many more families are eligible to receive child care assistance than participate. Approximately 27,000 children age birth to five fall below the income eligibility, yet only 7 percent receive child care assistance.20,21 For school-age children, about 31,000 children fall below the income eligibility, yet only 5 percent receive child care assistance. Low participation rates for child care assistance are a common trend across the country, however, South Dakota falls quite a bit lower than the national average of 23 percent.22 South Dakota’s rates are lower than neighboring states too, signaling additional barriers keeping families from using this program. Removing barriers and improving access to the child care assistance program is an important strategy for addressing child care challenges across the state.

Strategy #1: Improve how providers are paid for child care assistance.

Providers are reimbursed a set rate for a child eligible for child care assistance. This amount is based on market rate surveys, which reflect the typical cost providers charge throughout the state. However, the market rate does not reflect the true cost of caring for a child if higher wages and benefits were factored in. One way to improve the reimbursement structure long-term is to consider a cost modeling approach, which reimburses providers more closely for the true cost of care. Policymakers can commit to funding a child care cost modeling study as the first step to implement a cost modeling reimbursement system.

Payments to providers can be improved while working within the current market rate system. The state could consider increasing reimbursement rates for certain groups. For example, a higher rate for infant and toddler participants could incentivize programs to offer more slots for young children, an age group that is often the hardest to find care for. North Dakota recently invested $15 million over the next two years to increase the reimbursement rate for infant and toddler participants in their child care assistance program.23

Strategy #2: Support the child care workforce.

Child care providers are undervalued for the skilled and essential care they provide to the youngest South Dakotans. Policies and programs that support the child care workforce through higher pay and benefits can help programs recruit and retain skilled workers. For example, South Dakota can make child care workers eligible for the CCAP regardless of income. In 2022, Kentucky was the first state to implement this type of eligibility for child care workers and has helped 3,200 parents and 5,600 children in its first year.24,25 In South Dakota, 1,700 parents working in early childhood and 2,400 children could benefit from expanded categorical eligibility like Kentucky.

South Dakota could consider a program to directly support higher pay for child care workers. Minnesota implemented a grant program in 2023 where regulated providers receive monthly payments to increase early childhood education compensation.26 Minnesota’s program anticipates providers can receive about $375 per full time staff per month, or about $4,500 per year to boost child care pay. Many states have programs to provide one-time bonuses, stipends, or tax credits to child care workers that provide a smaller boost to pay. While these small boosts to pay can help, a larger scale investment to raise child care pay, like Minnesota’s monthly program, is needed to move the needle on recruitment and retention. For example, Montana implemented a one-time program where child care workers were eligible for up to a $1,600 stipend in 2023, the equivalent of a $0.77 per hour increase if working full time.27 Without ongoing funding, these one-time bonuses are only short-term boosts for workers and not long-term strategies to elevate the pay for child care workers.

Strategy #3: Make it easier for families to access Child Care Assistance.

Each family situation is unique, which might explain why they may not participate in the CCAP. For some families, they could greatly benefit from assistance paying for child care but are just above the eligibility guidelines. For example, a family of three at 250 percent of the federal poverty level ($62,150 per year) is not currently eligible but spends 13 percent of their income on child care at a center.28

South Dakota also requires families to cooperate with the Division of Child Support and maintain an active child support enforcement case as a condition of eligibility, if applicable to the family. Meeting the child support enforcement guideline creates more barriers for more vulnerable families, including single-parent families and teen parents.29 States have the flexibility to remove child support enforcement as an eligibility requirement for the CCAP, and three neighboring states do not have child support enforcement as an eligibility requirement: Wyoming, North Dakota, and Iowa.30

Moving the needle on child care in South Dakota requires more state investment.

More state investment in child care is needed to make significant shifts in child care access and affordability in South Dakota. Many other states invested additional state dollars to improve and expand child care assistance and support higher pay and benefits for child care workers.

- Montana committed $14 million in state dollars over the next two years to expand eligibility and lower copays for the CCAP. 31

- North Dakota committed $66 million over the next two years for a variety of improvements to the CCAP, including expanded eligibility, lower copays for families and higher payments to providers.23

- Minnesota invested $1.3 billion over four years to improve affordability of child care and $316 million over two years to create a child care worker compensation program.32

A state investment should accompany policy strategies identified in this report to improve access and affordability of child care in South Dakota.

Footnotes

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Total Population by Child and Adult Populations in South Dakota,” 2022.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Children Under Age 6 With All Available Parents in the Labor Force in South Dakota,” 2022.

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “Licensing and Registration Information,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Licensed or Registered Child Care Providers in South Dakota,” 2023; KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Licensed or Registered Child Care Capacity in South Dakota,” 2023; KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Licensed Before and After School Programs in South Dakota,” 2023; KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Licensed Before and After School Program Capacity in South Dakota,” 2023.

- In state fiscal year 2023, 34 counties have no licensed school-age programs and eight counties have no licensed or registered programs. Five counties have no licensed or registered programs overall: Harding, Jerauld, Jones, Sanborn, and Sully.

- Brookings Economic Development Corporation, “Brookings County Child Care Survey,” May 2020.

- The survey found 48 percent of slots (36 percent from unregistered and 12 percent from family or friend) were not represented in the licensed/registration data or Head Start. Using data available at the time of publishing our 2021 report, Brookings had a demand of 1,883 children age birth to five. Using this estimate, (48%*1,886) means there are an estimated 904 unaccounted slots. Adding this to the known supply of 796, there is an estimated total of 1,700 child care slots, which meets 90 percent of the demand. For full documentation of this calculation, see South Dakota KIDS COUNT, “A Modern Economy Depends on Child Care. South Dakota Can Make It Affordable and Accessible,” Dec., 2021.

- Child Care Aware of America, “Child Care Affordability in South Dakota,” 2022.

- Sioux Falls Childcare Collaborative, “Community Childcare Initiative Final Report,” Jun. 2023.

- Median family income by race is from table B19113A—B19113I. U.S. Census Bureau, “Median Family Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars), 2018-2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19112,” accessed on Dec. 7, 2023.

- Lloyd, C., Carlson, J., Barnett, H., Shaw, S., Logan, D., “Mary Pauper: A Historical Exploration of Early Care and Education Compensation, Policy, and Solutions,” Child Trends, Sep. 2021.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “May 2022 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, South Dakota,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.

- U.S. Office of the Assistance Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2023,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “May 2020 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, South Dakota,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “CPI Inflation Calculator.”

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “South Dakota Child Care Market Rate Report,” 2022.

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For South Dakota FFY 2022-2024.”

- South Dakota Department of Social Services, “South Dakota 2023 Child Care Subsidy Co-Payments, Effective March 1, 2023.”

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Child Care Assistance Recipients in South Dakota,” 2023.

- Breakdown of Child Care Assistance Recipients by age, as of Aug. 16, 2023: 1,882 children birth to 5 and 1,430 children age 6 and older. Menning, L., South Dakota Department of Social Services, “RE: Child care assistance by age,” email to Xanna Burg, South Dakota KIDS COUNT, Aug. 18, 2023, on file with author.

- Eligible children (denominator of percentage) is calculated as the number of children matching each age category based on 2022 population estimates multiplied by the percent of children living below 200 percent of the federal poverty level from table B17024. KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Child Population by Single Year of Age in South Dakota,” 2022. U.S. Census Bureau, “Age by Ratio of Income to Poverty Level in the Past 12 Months, 2018-2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B17024,” accessed on Dec. 7, 2023.

- Chien, N. “Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2019,” Office of the Assistance Secretary for Planning & Evaluation, Sep. 2022.

- North Dakota KIDS COUNT, “2023 Legislative Session: Children’s Well-Being Bills,” Aug. 2023.

- Vanover, S., “Celebrating New Benefits for Child Care Employees,” Kentucky Youth Advocates, Sep. 2022.

- Powell, A., Dade, A., “What the Bluegrass State Can Teach Us About Increasing Access to Child Care,” Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Oct. 2023.

- Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Compensation Support Payments,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.

- Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Child Care Workforce Stipends for Teaching & Caregiving Staff,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.

- Average yearly cost for center-based care ($7,862) divided by yearly income for 250 percent of federal poverty level ($62,150).

- Zero to Three, “Hurting Families That Need It Most,” Sep. 2022.

- Selekman, R., Holcomb, P., “Child Support Cooperation Requirements in Child Care Subsidy Programs and SNAP: Key Policy Considerations,” Mathematica Policy Research, Oct. 2018.

- O’Loughlin, H., “HB 648: Bridging the Gap to Childcare,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, Jun. 27, 2023.

- Minnesota’s Children’s Cabinet, “2023 Legislative Wins for Children and Families,” accessed on Dec. 5, 2023.